Project 1: Restorative Justice Program in a K-8 School

Problem and Rationale

“If crime is a wound, justice should be healing.” Howard Zehr, widely known as the grandfather of restorative justice, and one of the founders of the growing movement in North America, advocates for a paradigm shift in thinking about how we respond, as societies, to harm. When crime or injustices occur in our schools, currently, most schools (and the criminal “justice” system) ask questions like: “What rule was broken? Who broke it? What punishment is warranted?” (CCEJ Training, 2013). Conversely, schools using restorative practices in schools ask the following questions: “Who was harmed? What are the needs and responsibilities of those affected? How do all affected parties together address needs and repair harm?” (CCEJ Training, 2013). These questions demonstrate a restorative cultural shift that should occur in the way we approach parents, families, students and all stakeholders that experience harm and conflicts. Currently, there is little research that examines the impact of restorative justice practices as an alternative or partial alternative to zero-tolerance policies at schools with predominantly students of color. There is none that look at these practices within a school that has an inclusion model for special education or at a K-8 school. Additionally, most of the research around restorative practices in schools in the United States has been in white communities.

“If crime is a wound, justice should be healing.” Howard Zehr, widely known as the grandfather of restorative justice, and one of the founders of the growing movement in North America, advocates for a paradigm shift in thinking about how we respond, as societies, to harm. When crime or injustices occur in our schools, currently, most schools (and the criminal “justice” system) ask questions like: “What rule was broken? Who broke it? What punishment is warranted?” (CCEJ Training, 2013). Conversely, schools using restorative practices in schools ask the following questions: “Who was harmed? What are the needs and responsibilities of those affected? How do all affected parties together address needs and repair harm?” (CCEJ Training, 2013). These questions demonstrate a restorative cultural shift that should occur in the way we approach parents, families, students and all stakeholders that experience harm and conflicts. Currently, there is little research that examines the impact of restorative justice practices as an alternative or partial alternative to zero-tolerance policies at schools with predominantly students of color. There is none that look at these practices within a school that has an inclusion model for special education or at a K-8 school. Additionally, most of the research around restorative practices in schools in the United States has been in white communities.

Sandra Cisneros Learning Academy, like a majority of public schools in the United States, has depended on zero-tolerance polices to curve and minimize negative behavior. Despite the fact there is significant research pointing to the ineffectiveness of zero-tolerance policies in schools, these disciplinary policies have expanded in school districts nationwide, negatively affecting students of color (Schiff, 2013). Schiff explains that schools have failed to improve school cultures and environments through the use of suspensions, detentions, expulsion and other punitive responses. In other words, if schools redefined relationships of power and responded to student, parent and community needs in a collaborative and inclusive manner, youth would find school a place of more relevance. A push has been made in the last two decades to roll out zero-tolerance policies in our schools, yet Sumner (2010) states that no research has found that suspending or expelling misbehaving students for mundane and non-violent misbehavior improves school safety or student behavior. In fact, when these students are out of the classroom and at home, they have fewer opportunities to learn, and often result in finding themselves following a progression from schools, to juvenile hall, to the juvenile system, also known as the school-to-prison pipeline (Advancement Project, 2010).

Sandra Cisneros Learning Academy, like a majority of public schools in the United States, has depended on zero-tolerance polices to curve and minimize negative behavior. Despite the fact there is significant research pointing to the ineffectiveness of zero-tolerance policies in schools, these disciplinary policies have expanded in school districts nationwide, negatively affecting students of color (Schiff, 2013). Schiff explains that schools have failed to improve school cultures and environments through the use of suspensions, detentions, expulsion and other punitive responses. In other words, if schools redefined relationships of power and responded to student, parent and community needs in a collaborative and inclusive manner, youth would find school a place of more relevance. A push has been made in the last two decades to roll out zero-tolerance policies in our schools, yet Sumner (2010) states that no research has found that suspending or expelling misbehaving students for mundane and non-violent misbehavior improves school safety or student behavior. In fact, when these students are out of the classroom and at home, they have fewer opportunities to learn, and often result in finding themselves following a progression from schools, to juvenile hall, to the juvenile system, also known as the school-to-prison pipeline (Advancement Project, 2010).

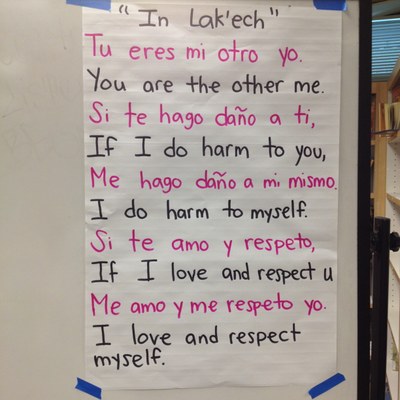

My project was focused on implementing a spectrum of restorative practices at an urban, low-income school with predominantly students of color. At Sandra Cisneros Learning Academy, our restorative justice model was rolled out over the course of 10 months. Beginning in the summer of 2013 when I attended a Community Building training with the California Conference for Equity and Justice we started our journey of learning, and grappling with a new way of approaching various relationships at our school site. Making this paradigm shift was a constant attempt to minimize the zero-tolerance policies, such as, expulsions, out of school suspension, in school suspensions, detentions and other punitive consequences to respond to misbehavior but it also became a cultural shift experienced by adults, not just students.

Challenges and Changes

Challenges and Changes

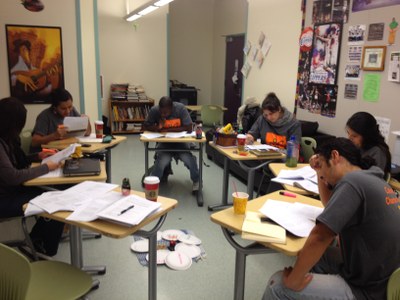

Challenges are to be expected with change, and especially when asking it asks teachers to engage in a school-wide change initiative. Initially, getting buy-in from teachers was a challenge. Weekly community building circles were not being practiced by every teacher and there was a lot of skepticism around whether these practices could change student behavior and reduce misbehavior in the classroom. I believe there were two variables contributing to getting teacher buy-in. First, the RJ Task Force was comprised of the vice principal, dean, office manager, parent coordinator, and 4 teacher leaders. One of the teacher leaders is a resource teacher, another a 1st grade bilingual teacher, a 5th grade teacher and 7th/8th grade teacher. On several occasions after the Task Force planned and led two professional developments, teachers commented on the success of having such a diverse team of stakeholders working towards a collective vision and some even mentioned wanting to have a similar structure or committees for deciding curriculum and instruction. I strongly believe that this combined with numerous successful teacher/staff circles led to the buy-in of these RJ practices. You can walk through our campus and see teachers, campus aids, the dean, vice principals, and students leading circles and doing it with ease and confidence. They have acquired the language and most importantly, believe in the practices.

Another challenge was getting some members of the Task Force to fully buy-in to RJ practices and moving towards a school rollout. One person in particular was hesitant to make some of these cultural shifts and changes but was essential in making this program a success. Most of the RJ work should happen in the classroom with teachers in the classroom, through community building circles. This work is preventative and requires that teachers allow themselves to become transparent and vulnerable with students. In doing this and building honest and open relationships through honest and open conversations, a majority of teachers did this. Another important element after teacher buy-in was having the dean feel comfortable with Harm and Conflict circles as an approach to student discipline. Initially, there was some resistance but after supporting him in planning and facilitating his first few Harm and Conflict circles, the dean ran with this restorative justice approach as an alternative to traditional guardian-student-dean meetings as a way to hold meetings with students. This became a best practice for him and eventually was so bought-in that he presented on this practice to deans and vice principals in the organization.

Another challenge was getting some members of the Task Force to fully buy-in to RJ practices and moving towards a school rollout. One person in particular was hesitant to make some of these cultural shifts and changes but was essential in making this program a success. Most of the RJ work should happen in the classroom with teachers in the classroom, through community building circles. This work is preventative and requires that teachers allow themselves to become transparent and vulnerable with students. In doing this and building honest and open relationships through honest and open conversations, a majority of teachers did this. Another important element after teacher buy-in was having the dean feel comfortable with Harm and Conflict circles as an approach to student discipline. Initially, there was some resistance but after supporting him in planning and facilitating his first few Harm and Conflict circles, the dean ran with this restorative justice approach as an alternative to traditional guardian-student-dean meetings as a way to hold meetings with students. This became a best practice for him and eventually was so bought-in that he presented on this practice to deans and vice principals in the organization.

Main Activities

- Community Building Training Over the Summer: I attended a 2-day community building training grounding me in RJ practices.

- Forming a Task Force: I approached various teachers, staff and stakeholders about joining a task force to attend a weekend community building training. This was the beginning of building buy-in and a team to support this school-wide reform.

- Task Force Community Building Training: Task force members participated in a full-day community building circle training.

- Task Force Retreats: I planned and facilitated 3 Task Force Retreats/meetings where I trained members on the research of RJ practices and we planned teacher PDs. We developed tools for teachers to use K-8 to have successful community building experiences in their classrooms.

- Initial Whole PD Training: The Task Force presented community building circles to teachers and a larger historical and pedagogical framework for circle in schools.

- Support/Train Dean in RJ Practices: I attended and supported the dean in his initial Harm and Conflict circles, providing him with the framework, questions and structures to hold these with parents and students.

- Official RJ Rollout Teacher Professional Development: The Task Force planned and led a 2-hour PD with teachers where teachers were given time to plan their own circle lessons and engage in a conversation around this shift towards RJ practices.

- Staff Circles During Professional Development: The Task Force began planning and leading circles and eventually grade level teams were asked to facilitate circle with teachers creating an engaging and sustainable model for holding circle with staff.

- One-on-one Teacher Support: I supported teachers who approached me by helping them plan community building and Harm and Conflict Circle lessons.

- UCLA Teacher Education Program Cohort Presentation: I planned and lead a 3-hour workshop for a cohort of prospective teachers in UCLA’s Teacher Education Program. The workshop began with a circle, then I provided teachers with a historical framework RJ practices and finished with a Q & A session. Various of these teachers visited my classroom to experience a circle with students.

- Staff Harm and Conflict Circles: On various occasions teacher Harm and Conflict circles were requested as a way to address conflict amongst staff members.

- Parent Workshop Circles: The vice principal and parent coordinator held community building circles with the parents on multiple occasions.

- Promising Practice Conference: I worked with the resource teacher and a few members of the Task Force to plan and lead a workshop on RJ practices at a Camino-wide conference on promising practices.

- Harm and Conflict Training: The parent coordinator, vice principal, dean and myself attended a 3-day Harm and Conflict training in February to strengthen our practices.

PowerPoint Used for Official Rollout Professional Development:

Prezi Used for Teacher Education Program (TEP) Presentation:

Video for Promising Practice Conference:

Outcomes and Data

A consideration for my project was the degree of restorativeness that our school sight adopted, since restorative practices fall along a continuum, from fully restorative to non-restorative (Zehr, 2002). We conducted initial surveys with teachers around their familiarity with restorative justice practices and circle.

Initial Survey Data:

The initial teacher survey response was 85% (22/26) and revealed some interesting information, around restorative practices. Important to note is that both the survey and the focus group were conducted after teachers had received one 2-hour PD on restorative justice practices. In response to the question that asked how often a teacher holds a council/circle, 15 (68%) of teachers have council once a week, 3 (14%) have it two times a week, 1 (4.5%) hold it three times a week, 1 (4.5%) holds it five times a week and 2 (10%) do not hold a council/circle. Of these teachers, 1 (5%) said they feel very comfortable holding a circle/council, 2 (9%) comfortable, 13 (55%) feel somewhat comfortable, 4 (27%) feel uncomfortable, and 2 (5%) teachers feel very uncomfortable. This information will likely inform the restorative justice’s task force next steps around professional development and teacher support with the community building council/circle. One teacher wrote in the survey in regards to restorative practices: “It's a positive shift in the right direction. It helps us acknowledge and nurture students humanity, it teaches them skills that they will need to resolve conflict in the future, and it will eventually lead to less suspensions on our campus.” The majority of teachers held similar views to this teacher’s comments around restorative justice practices. Only one teacher spoke negatively restorative justice practices and does not feel that they will be effective at changing student behavior.

Post Survey Data:

The end of the year survey response was 100% (30/30). This survey included the administrators, which the first did not. In response to the question that asked how often a teacher holds a council/circle, 23 (76.67%) of teachers have council once a week, and 7 (23.33%) said it was not applicable, 4 administrators took the survey so that might account for the N/A responses to some of the questions. Additionally, our resource teachers (3) who push-into the classrooms and do not technically have their own room, so this may also account for some of the N/A responses. Of the responses, 10 (34.48%) said they feel very comfortable holding a circle, 11 (37.93%) comfortable, 8 (27.59%) feel somewhat comfortable, 0 (0%) feel uncomfortable, and 0 (0%) teachers feel very uncomfortable. There was a significant shift in teacher's comfort levels with holding circle and I would attribute this to the PDs and asking teacher's to facilitate/practice planning and holding circle with the teachers. Furthermore, members of the task force frequently assisted grade-level teams with planning for circle.

Some of the teacher responses to the end-of-year survey:

- "Restorative justice has improved the communication with students and their ability to self-regulate their behavior."

- "Honestly, my students crave our circles. I feel like it's the only place where they feel safe to share what is going on with them. Before, it just felt like students were tattle tailing on one another. Now, I feel like the students are much more empathetic towards one another because of what the student shared in circle. That being said, I feel like certain issues that are much more deep rooted (i.e., racism) are going to take much more than just a few circles to heal. I'd love to know if we could have more than 1 pd where we could record and then observe different classrooms' RJ circles."

- "Community circles for community building hoping to use circles in back to school night next year or some other early parent conference"

- "Teachers are more connected to one another, and there is a greater sense of community amongst teachers. Students ask to hold circle and it's an opportunity to connect with students on an emotional and personal level."

- "I feel like at several other schools, many of our heart students would have been expelled or simply ignored. we really put a TON of care into our students, especially our heart students"

- "I feel there is a stronger community and more empathy in my classroom. When we miss a circle on a Friday the kids are always quick to ask me why and if we can make up that time on Monday. I also feel like I've gotten to know more of my colleagues this year which has been amazing, it feels like we are a little family."

- "I love that we have implemented circle into our PD meetings. It really builds community and brings us closer together as human beings. My students look forward to circle and I have learned to utilize this strategy within my lessons and discussions."

- "I feel like I interact with both students and staff in a different way because it humanizes us. We can all make mistakes and these circles have helped built empathy and a sense of connection to our staff and students that I didn't have before."

- "We have gotten to know each other much better as individuals. I think we have grown closer to each other because we know each other as people. It gave our school the "Corazon" that it was missing."

Pre and Post Suspension Data:

The suspension rate from July-January 12/13 vs 13/14:

Suspension Rate 12-13: 5.1%,

Suspension Rate 13-14: 2.2%,

Single Student Suspension Rate 13-14: 2.2%

The dean, held Harm and Conflict: approximately 60-80

Pre expulsion circles: 5-8

Re-entry circles: 2

Hindsight

To continue supporting students, families and teachers in this work, the Task Force should consider inviting a parent leader to be an active member in the Task Force and to attend retreats and meetings. Additionally, having a community member and a student present would ensure that all major stakeholder's voices were heard in the implementation of restorative justice practices.

To better serve our students who face disciplinary consequences at our school site, I would have set time aside during our Task Force meetings to identify students in need of a smaller circle of support made up of teachers and staff members. Proactively meeting with struggling students and creating a network of support could deter any future instances of misbehavior.

Reflection as a Leader

My identity as a leader developed significantly because I was able to implement a vision, affecting students, staff and the entire school community (Standard 1). Essentially, I was able to move from an individual vision towards a collective vision. I would say that teachers and those on the Task Force appreciated the honesty, openness and transparency that I brought to the team. Additionally, we were always very productive and were able to accomplish so much that it was a rewarding experience for those involved in the process. In fact, many teachers echoed the need for other similarly structured teams at the school so that teachers and other stakeholders could have an active voice in areas such as budgetary and curricular decisions. Working with the task force allowed me to support teachers in the classroom with planning their community building circle lessons, with the Dean in facilitating Harm and Conflict Circles, with the Parent Coordinator by supporting parents and directly with students; giving me a pulse on a majority of the school community (Standard 4).

Identity as a Leader

Identity as a Leader

My strength as a leader was empowering others involved in the work to take active roles in moving along the vision. Prior to being on the Task Force, the resource teacher had never facilitated any PDs, but took an active role in the Promising Practice Presentation Workshop and at the second staff Restorative Justice PD. Empowering educators to take ownership of the work is crucial when working towards accomplishing a collective goal. Recognizing and bringing out people's own leadership strengths is crucial because no work can be done alone. Building understanding of the project and my individual vision was vastly important in moving towards a collective understanding and vision and I accomplished this through circle. Circle is a structure that democratizes spaces by giving everyone a shared opportunity to voice their ideas and reflections. Circle creates spaces of care, and empathy. Being a circle keeper and developing more than 30 adult's capacities to facilitate circle built collective care and created an abundance of authentic connections and networks at our school site. Realizing this strength of a facilitator within the educators helped in creating a trusting and loving environment.

Connection to CSPEL

Standard 1: A school administrator is an educational leader who promotes the success of all students by facilitating the development, articulation, implementation, and stewardship of a vision of learning that is shared and supported by the school community

1.1 Develop a Shared Vision: Facilitate the development of a shared vision for the achievement of all students based upon data from multiple measures of student learning and relevant qualitative indicators. Communicate the shared vision so the entire school community understands and acts on the school’s mission to become a standard’s-based educational system. Use the influence of diversity to improve teaching and learning.

1.2 Plan and Implement Activities Around the Vision: Identify and address any barriers to accomplishing the vision. Shape school programs, plans, and activities to ensure that they are integrated, articulated through the grades, and consistent with the vision.

Standard 4: A school administrator is an educational leader who promotes the success of all students by collaborating with families and community members, responding to diverse community interests and needs, and mobilizing community resources.

4.1 Collaborate to Incorporate the Perspective of Families and Community Members: Recognize and respect the goals and aspirations of diverse family and community groups. Treat diverse community stakeholder groups with fairness and respect. Incorporate information about family and community expectations into school decision-making and activities.

Future Implications

It is my hope that the restorative justice practices and this model for approaching conflict and harm at our school site, will thrive and grow in the years to come. It is my hope that students and parents will become even more involved in the planning and development of this program and that they take more active roles in the Task Force. I anticipate that in the future, if we get all major stakeholders to be a part of the Task Force, that there will be a greater understanding, commitment and most importantly, increased positive relationships that help grow caring relationships at the school site that will work together to create positive change in the school community. Additionally, I would like to have a quarterly circle where community members, parents and students are invited to participate in a circle at the school. In order to provide parents, students and teachers with the necessary support in the area of restorative justice, there needs to be a full-time restorative justice coordinator; having a restorative justice program is hugely time consuming and at many schools, the dean has been replaced with an RJ coordinator.

PowerPoint used for Camino's Promising Practice Workshop:

Supporting Documents

Sample Circle Lessons Grades K-8