Leadership Fieldwork Project - Transformative Praxis

PROJECT SUMMARY

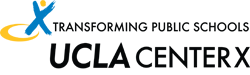

Transformative praxis is a critical theory of school culture, a method of affective reciprocity, an analytic framework, and a liberatory practice. I have derived this phrase and approach based on a reading of texts within the critical pedagogy tradition, action research, and community organizing. According to the People’s Education Movement, “The goal of transformative justice is to develop healing processes and re-create humanizing alternatives to the root causes of an oppressive situation. This process recognizes how colonial ideology and systems harm everybody. Transformative praxis creates accountability to meet all parties' needs in order to call for the justice we seek to have, not the current one that exists.” This quote identifies 3 manifestations of oppression and suggests 3 corresponding ways of overcoming oppression: mindsets, relationships, and deeds.

This leadership fieldwork project on transformative praxis explored how social justice educators can combat oppressive forces and promote freedom and justice through a critical subjectivity, an identity that elides normativity, ideology, and hegemony. This approach proposed several questions: What hegemonic ideologies are currently at play in our school culture? What critical mindsets allow us to expose power? How do we democratically engage young people and communities? What collective strategies will allow us to transform ourselves, transform others, and transform the world? Three practices responding to these questions were implemented at YouthBuild Charter School of California (YCSC):

- Critical Inquiry

- Restorative Justice

- Participatory Action

Transformative praxis emerges through these 3 sets of practices:

YCSC, where I work as an Assistant Principal, has 19 campuses across Southern California. The transformative praxis project was piloted at 2 out of the 9 campuses that I supervise, in El Monte and Norwalk. In all aspects of this fieldwork project, I took a participatory approach to the process. That is, I facilitated processes for teachers and students to reflect and act. Participants were valued for their assets and insights and they were engaged as leaders at their school campuses. My own leadership consisted in facilitating processes for others to engage in democratic leadership.

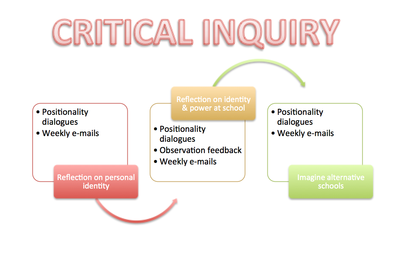

CRITICAL INQUIRY (CI)

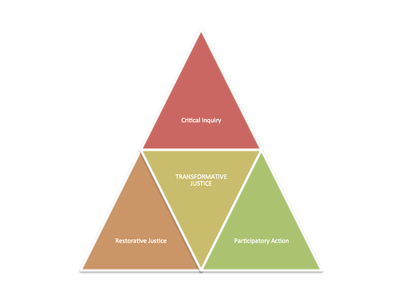

Critical inquiry asks educators to reflect on the role of positionality at school. Examining positionality entail examining how certain identities assign power and privilege, while others marginalize. Educators dialogued about their own identities, those of students, and how the curriculum reflected and interacted with those identities. Tyrone Howard provides a framework for critical reflection in an article titled “Culturally Relevant Pedagogy: Ingredients for Critical Teacher Reflection” (Howard, 2003). Howard argues that critical reflection about race is a precursor to implementing culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory impacts practice.

At my own school, I wanted to explore the intersectionality of multiple identities with a focus on gendered identities. I wanted to see how ideologies around race, class, and sexuality, for example, cross hatch with those of a gendered body. Richard Milner uses race reflective journaling and a questionnaire to help teachers explore their identity and biases. Milner explains that the journaling is prompted by guiding questions that explore identity (2003). He also provides a model for critically reflective dialogues, which he calls critically engaged dialogues (Milner, 2003). I adapted these deliberative and dialogic techniques to promote reflection, conversation, and action at YCSC.

How does one create a critical mindset about ones own practices? And, furthermore, how does one create a critical mindset about social and political marginalization in and out of schools? In my leadership project, I explored student and teacher identity, but, also, I thought purposefully with my colleagues about how issues of ideology, identity, and power should be accounted for in teacher practice and student learning. Critical inquiry, as I developed these practices, differs from reflections on positionality. Teachers and counselors reflected on issues of power in their own identity, following a positionality model that examine personal ideas and biases. But I also sought to use private reflect as a forum to examine public issues. With teachers, I wanted to discuss issues of identity in education, in school policies, practices, and structures.

CI Project Implementation

Early in my discussions with the Norwalk and El Monte staff members, we determined that we could measure the impact of critical inquiry on students through a microaggressions journal that I kept as part of a UCLA assignment. That is, if teachers were more reflective about their identities and issues of power, that reflection might translate to their work with students, and, in turn, might lead to my observation of fewer microaggressions by staff and students. Besides and beyond this collective goal, I hoped to use the journal to measure the impact of critical inquiry through teachers integrating issues of identity and power into the school curriculum.

I facilitated critical inquiry through 4 practices: positionality dialogues, classroom observations, microaggression journaling, and weekly e-mails with readings and resources.

- Positionality dialogues with staff

- Observation feedback on positionality

- Microaggressions journal

- Weekly e-mails with readings and resources

These 4 practices align to critical inquiry in the following ways:

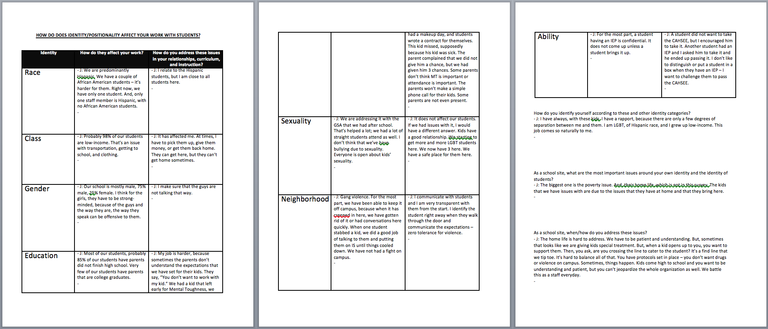

Positionality dialogues were held throughout the school year with each education team in Norwalk and El Monte as a whole and with individuals. I started by explaining my project and having a conversation about the purpose of the dialogues.Next, I asked staff members to fill out a survey on issues of identity, how it impact their relationships with students, and how they address identity as a school. Specifically, I asked to two questions about the identity categories of race, class, gender, education, sexuality, neighborhood, and ability.

- How do they affect your work?

- How do you address these issues in your relationships, curriculum, and instruction?

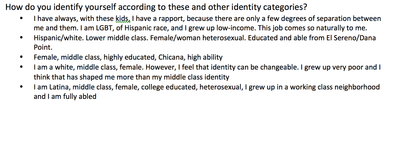

Additionally, I asked each staff member three additional questions:

- How do you identify yourself according to these and other identity categories?

- As a school site, what are the most important issues around your own identity and the identity of students?

- As a school site, when/how do you address these issues?

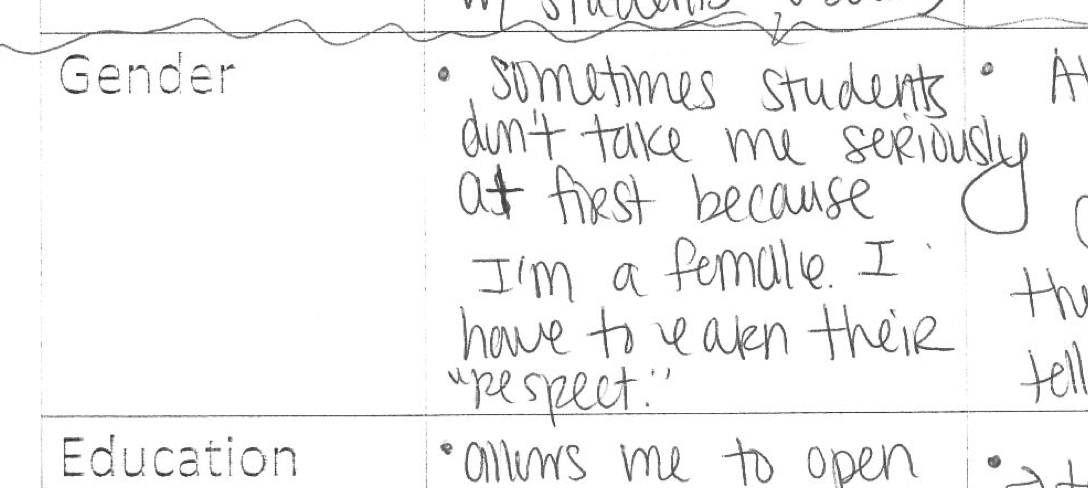

Below, I provide an example of a survey completed by a staff member:

After collecting the surveys, I compiled the responses for each campus and reviewed them with the staff members. Below, I documented the collective responses of El Monte staff members to issues of race at their school.

Below, I document the collective response by staff members at one site on how they embodied various identities:

The individual responses were sources of very valuable conversations with staff members as I met formally and informally with them.

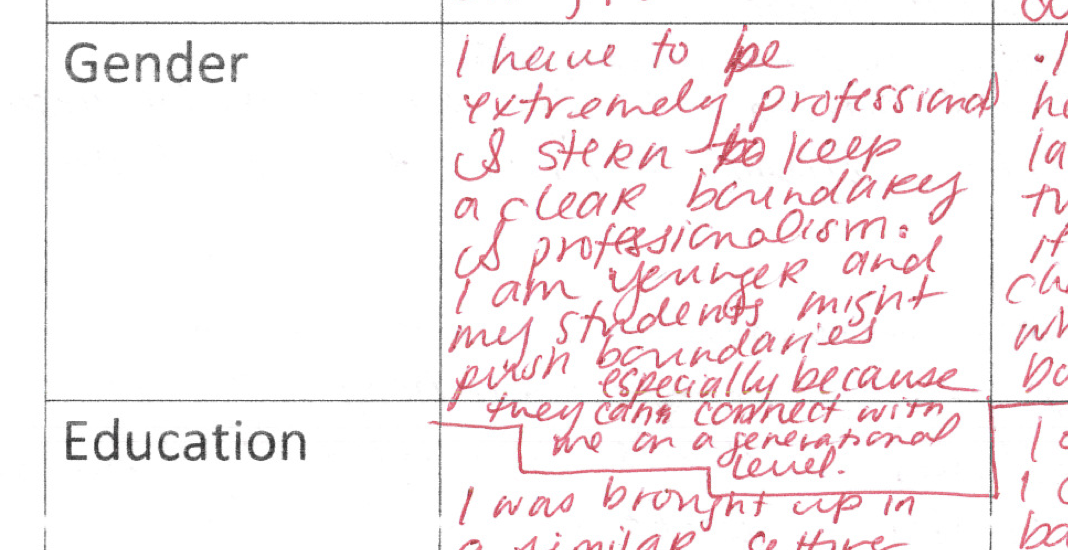

After I compiled the responses, two issues were particularly notable. First, most El Monte staff members did not know that sexuality refers to issues relating to the LGBTQ community. Second, the points of the greatest disjuncture or tension existed around gendered identities. Several female staff members felt like they were not as well respected because of their gender.

One teacher felt like she had to compensate for her gender by being extra professional and stern:

Another teacher felt less respected because of her gender. She also felt like she had to compensate for being woman:

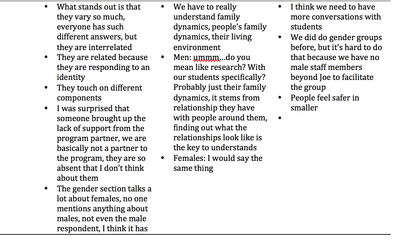

Finally, I interviewed each staff member to gather their reflections on the survey results and to ask what more information we as a staff could gather in order to understand gender dynamics better. We also discussed what next steps we should take to address issues of identity and gender. Below, I document a reflection by one staff member:

This final interview focused on identifying next steps we could take as a school to better address issues around identity, with a focus on gender. Some of the next steps recommended included the following:

- Interviewing students on their experiences

- Holding workshops about respect and identity

- Facilitating gender discussion circles

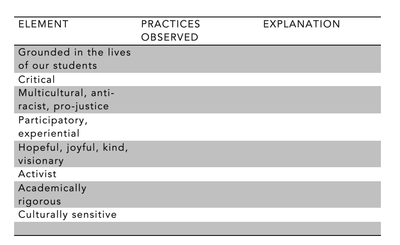

After initiating the positionality dialogues, I conducted several formal and informal classroom observations of teachers in Norwalk and El Monte. I developed an observation form that would help me identify best practices in education for social justice. This form helped me notice identity dynamics within a classroom, between the teacher and students and between students. Further aspects about the observation and feedback process will be explained in the project webpage titled "Curriculum & Instruction." At the top of the form, I introduce and define the philosophy behind this new observation form:

In the center portion of the form, I list the element that I will observe when I visit classrooms:

As described earlier, I kept a microaggressions journal this year to document unconscious and/or unintended acts of tension due to race, gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, and ability. I had two goals for this journal:

- Identify types of microaggression that reoccur at my school

- Have data to use as a discussion point with staff members

- Encourage staff members to take action when they witness a microaggression

- Take steps as a school community to address microaggressions

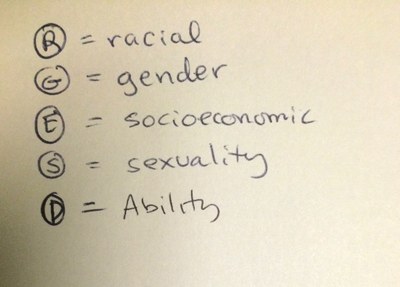

I used letters to code my observations according to the type of identity targeted by the microaggression:

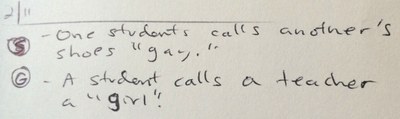

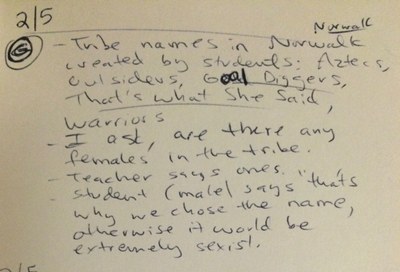

Below, I document two microaggressions. In the first, a student uses the word "gay" with a negative valence. In the second example, a student refers to an adult teacher as a "girl." After each incident, I was able to discuss with the staff that observed these how they could respond to such microaggressions.

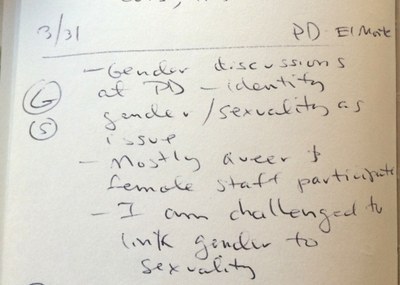

At several points in my microaggressions journal, I noted my own microaggressions. This process help me identify those unintended actions. One of my own microaggressions took place during a discussion that I led during the spring professional development for all YCSC campuses. This discussion took place over two days. Staff were invited during their lunch to sit with me and discuss issues of gender at our school. I noted two microagression. In the first, I noted that all of the participants in this discussion were female and/or LGBTQ, except for one male participant. This is an implicit microaggression.

In my journal, I noted how I exhibited a microaggression, as I did not make the natural links between gender and sexuality in these conversations. One of the staff members helpfully made those connections for the group.

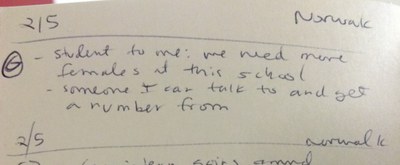

Most notably, both in Norwalk and El Monte, the most common microaggressions occurred around issues of gender. In Norwalk, these microaggressions were committed by male students. One male student, for example, walked into a room and asked a female teacher why the school does not enroll more female students. When the teacher asked why he asked this question, the student responded that he wanted more females to ask on dates.

In another incident at Norwalk, students were placed into "tribes" to meet weekly about personal and academic goals. Each tribe chose a unique name for itself. One tribe was made up of mostly male students. Only one female was in the tribe. The tribe also had a male staff leader. The tribe wanted to name itself "That's What She Said." The male staff member allowed this name to be chosen until I questioned him later that day. The named was changed.

In El Monte, both students and staff members committed verbal microaggressions around issues of gender. Notably, these microaggressions expressed the same idea, that female staff members are weak and need to be protected. In several incidents, female and male staff members would remark that they need more male staff members to protect the campus. While concern for safety is always warranted, these concerns seemed exaggerated and were always connected to issues of gender. Although El Monte has a high number of students that are gang-related, over the last 6 years, they have had a couple of fights on campus. On one occasion, a student asked me if the charter school would consider hiring security guards to protect the campus and make up for the lack of male staff members.

In sum, the microaggression journal keeping and the positionality reflections convinced me that gender is a recurring dynamic at my school.

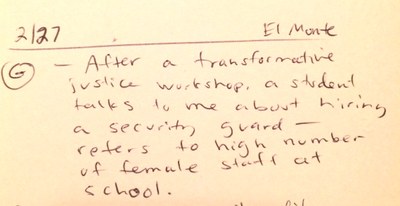

During the last school year, I attempted to send regular, weekly e-mails to the YCSC staff members that I supervise. I struggled to find a purpose for those e-mails and eventually stopped sending them. This year, in February, I began that practice again with two goals in mind: a) to regularly updating staff members about upcoming and past events and b) to share resources and readings around issues of identity in the educational field. The resources and readings were gathered from readings in class at UCLA, research I was reviewing on my own, and resources gathered by an organization in response to an event or issue. Resources linked to an event include LGBTQ curriculum to help teachers organize a Day of Silence event at their campus. I hoped that these e-mails, summarized below, would spur dialogues and reflection on issues of identity, positionality, education, curriculum, and practice.

Given my identification of gender as a recurring issue at YCSC, I focused several of my e-mails on sharing resources around that identity.

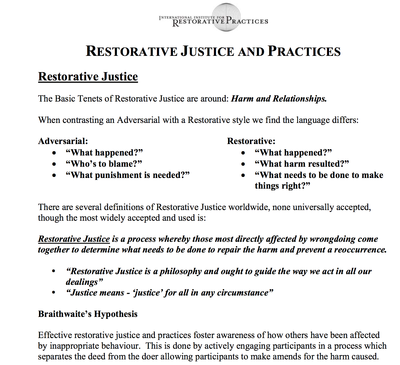

RESTORATIVE JUSTICE (RJ)

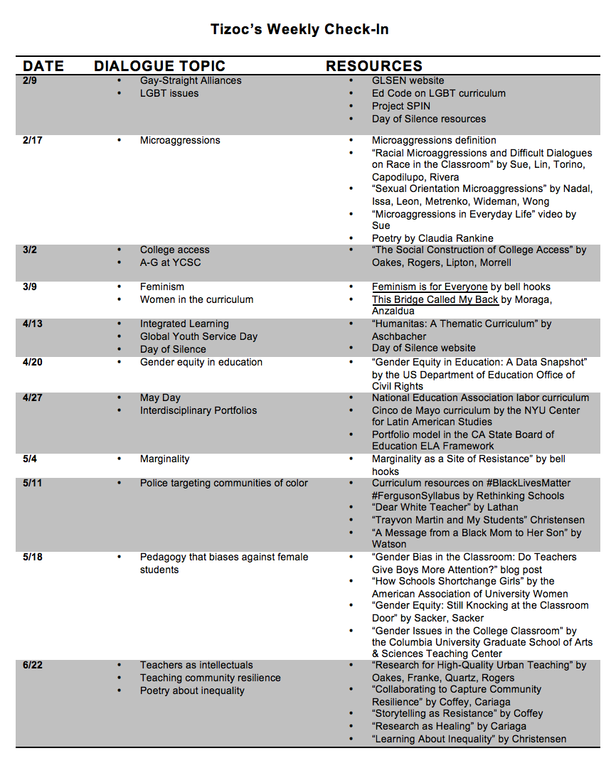

Restorative justice frameworks offer tools for community building, creating a positive school culture, and repairing harm due to conflict. At YouthBuild Charter School, we implement a model outlined by Ron and Roxanne Claassen in Discipline That Restores (2008). YouthBuild staff were first trained in restorative practices in July of 2010 by the Claassens. This model provides tool for community building inside of the classroom through respect agreements and conflict management processes. Since the first schoolwide training 5 years ago, there have been several follow-up workshops with the Claassens and trainings led by YCSC staff members who adapted the model.

This graphic summarizes the distinct practices involved in the Claassen restorative justice model:

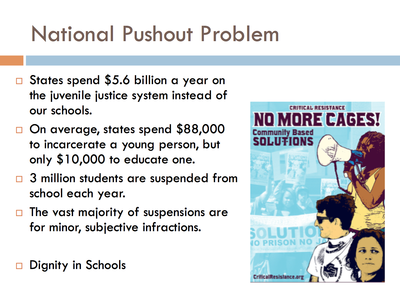

Additionally, last year, the entire school staff was trained in another model, called transformative justice, by the Youth Justice Coalition. The Youth Justice Coalition is partnered with YCSC and hosts our school staff in Inglewood. Three practices distinguish this transformative justice model from the Claassen one: a) an asset-based philosophy about youth leadership development, b) community circles to rebuild community in response to a conflict, and c) community organizing to combat forces that may be at the root of interpersonal conflicts.

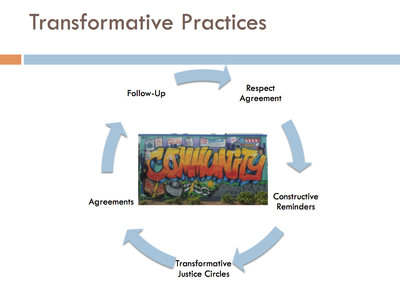

This graphic summarizes the various practices involved in transformative justice:

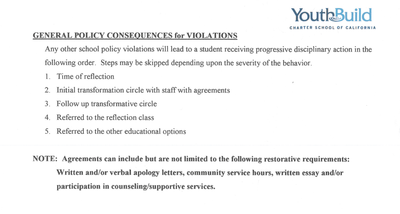

Norwalk staff members have been implementing the Claassen model. At the beginning of the year, the El Monte staff members adopted the harm and conflict circle model from the Youth Justice Coalition. At the beginning of this project, neither YCSC campus implemented their models with fidelity. In the winter, I conducted observations and surveys of staff, participated in staff meetings where discipline was discussed, and reviewed the policy manuals. The following paragraphs describe some of the benchmark data that I observed and collected.

In El Monte, only one teacher had created a Respect Agreement, a key practice in the Claassen restorative model. She did not post the agreement on the wall, as is recommended in order to make that document a part of daily class culture. Another teacher had an agreement posted, from last year. It was, however, hidden behind a television set.

In Norwalk, similarly, only one teacher had created a Respect Agreement. She posted the class Respect Agreement on a wall by her white board. On most other walls on the Norwalk campus, the staff posted a list of rules, which reflected a more disciplinary and normative mindset. None of these rules were collaboratively created by staff; each classroom and public space on campus had different rules.

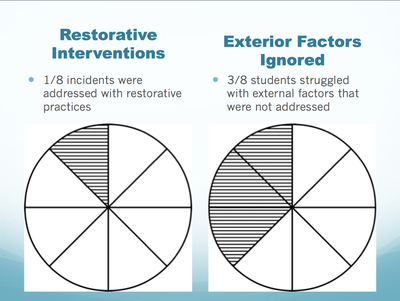

For a month, in the winter, the teachers at each school campus documented behavior incidents in their classroom. They also documented their responses to the behaviors. These behavior incidents were documented on a Google form. I used this data to determine whether and to what degree restorative practices were being used. This graph indicates that restorative practices were rarely used and that external home factors, that should be accounted for, were not addressed:

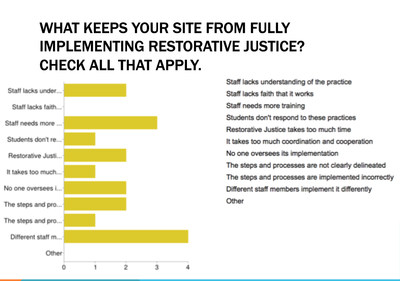

I also surveyed the school staff members to assess their understanding of restorative justice, their buy-in, and their desire for more training. According to this survey, school staff believed that restorative practices were effective, but they indicated that they needed more training. In the response below, staff members indicate identify three primary barrier to fully implementing restorative justice: differences in how staff members implement it, the need for more training, and a lack of understanding.

After collecting all of this benchmark data, I was able to begin the implementation phase of this portion of the fieldwork project.

RJ Project Implementation

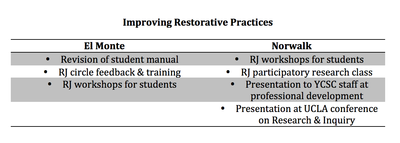

Improving restorative practices took different courses at the El Monte and at Norwalk campuses. Each campus implemented different practices and identified different needs for improvement. Given my participatory approach to this work, I facilitated spaces for teachers and students to identify their own goals and implement changes to their own school environments.

In El Monte, the staff members and I began by revising the campus student manual. During the assessment phase of my project, I noted that the written discipline policies did not include restorative language. We revised the El Monte student manual to explain their transformative justice processes.

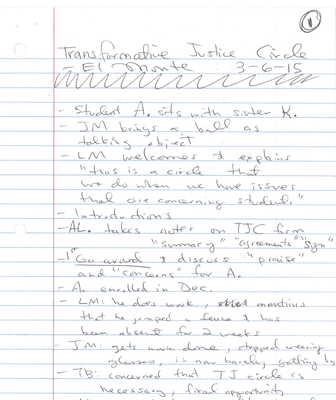

The practices in El Monte revolved around transformative justice circles. Other restorative models call this harm and conflict circles. The staff requested further feedback and training from me on circle facilitation. Below, I include a portion of the notes I took while I observed one of the transformative circles.

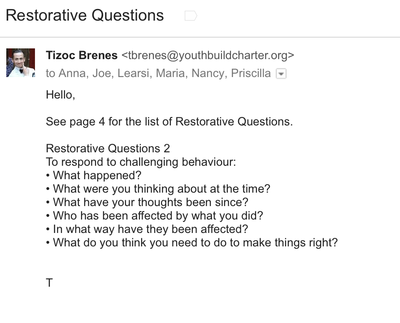

After observing the El Monte staff members facilitate transformative circles, I provided them with targeted feedback. I shared a circle facilitation process that I learned through the International Institute for Restorative Practices. This model provides a very clear and simple structure for circle facilitation.

In a follow-up e-mail and discussion, I highlighted the restorative questions that should structure the circle process:

In the final stage of improving practices in El Monte, we agreed to inform students about the transformative justice policies. We did this in two ways. First, the school staff organized a training around respect agreements with students. They did not create a new, collective respect agreement, but they set the groundwork to do so in the future.

Second, I led a workshop on Transformative Justice, where I explained the origin and philosophy of transformative justice practices. I outlined the specific practices and connected restorative justice to the disruption of the school-to-prison pipeline.

At the end of the workshop, I provided students with scenarios where a students was punished punitively. I asked them to suggest ways to use a transformative justice approach.

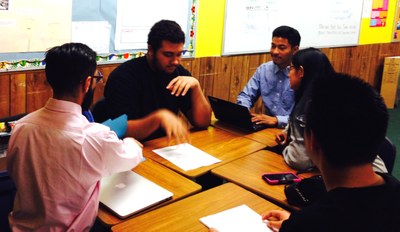

In Norwalk, I worked more collaboratively with both students and staff members. When I initiated my fieldwork, the English teacher was planning to teach a course for the second time on Restorative Justice. Early in her planning, I worked with her to design the class as a participatory action project. That is, students would conduct research on restorative practices at the school and recommend and implement changes to those practices. I visited the class regularly to collaborate with students.

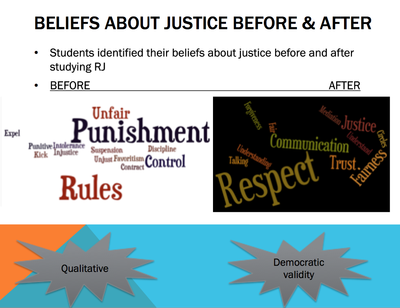

During the first unit of the class, students learned about the history and theory of restorative justice. I visited the class to observe some of these lessons and participate in conversations. At the end of the unit, students reflected on what they believed about justice before and after these lessons. In this picture, students documented the transformation of their beliefs:

During the second unit, I introduced my own research on restorative justice at the Norwalk site and different methods of collecting quantitative and qualitative research.

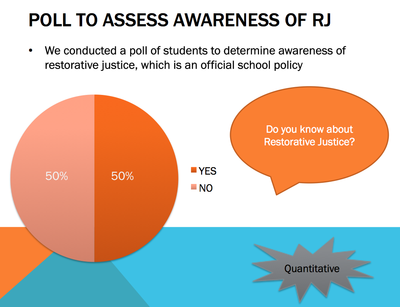

In the lessons that followed, students conducted their own research at the Norwalk campus. First, they took a poll about student and teacher awareness of restorative practices.

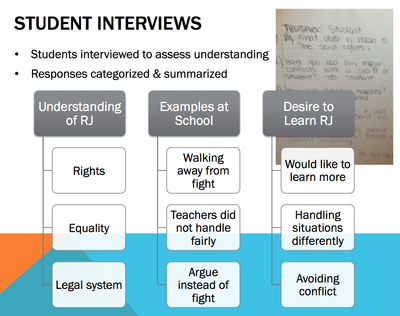

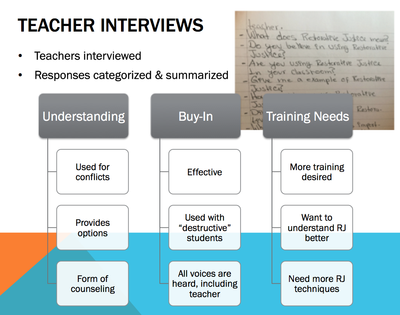

Then, they designed interview questions and conducted one-on-one interviews of teachers and students on campus. The students analyzed the responses to those interviews.

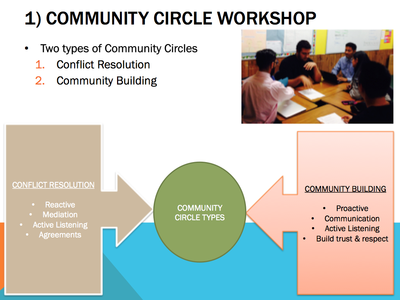

Based on deficits in student and teacher understanding, the Nowalk student researchers developed workshops on different aspects of restorative justice: communication, community circles, and the history and philosophy of restorative justice. Below, students outline their community circle workshop:

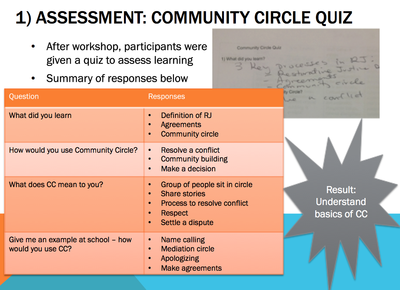

They collected data and feedback and assessments at the end of all 3 workshops. Below, students who facilitated the community circle workshop summarize the quiz results:

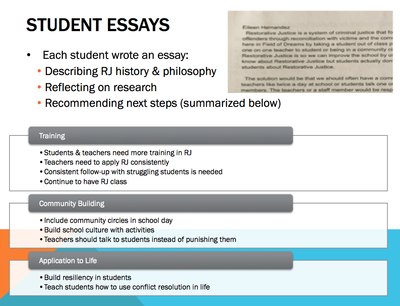

Students wrote essays summarizing their learning and recommending next steps in improving restorative practices at the Norwalk campus. The class analyzed and summarized the essay responses. Students recommended more training for students and teachers, community building activities, and skill building to help students apply these lessons to their lives:

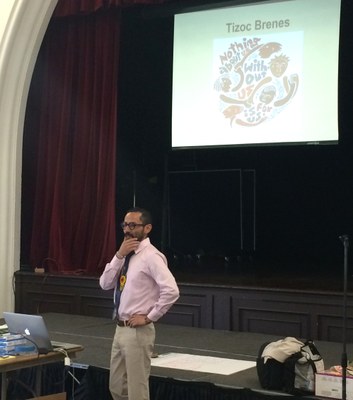

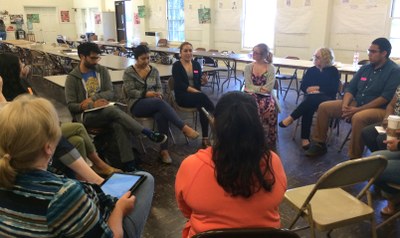

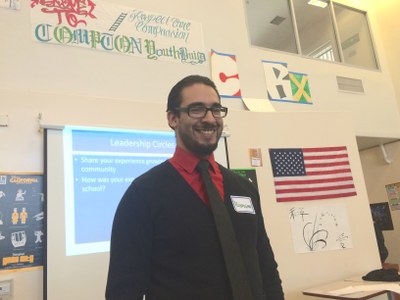

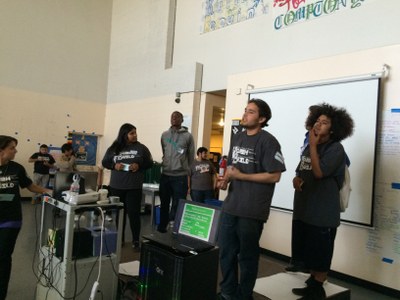

During the final phase of the restorative justice class in Norwalk, two opportunities materialized for students to share their work with a larger community. First, the teacher, a student, and I presented a workshop on participatory action and restorative justice at the spring professional development for all YCSC campuses. Approximately 15 staff members from campuses throughout the network attended our workshop. After the workshop, several staff members e-mail me to request our PowerPoint.

We started that workshop with a community circle:

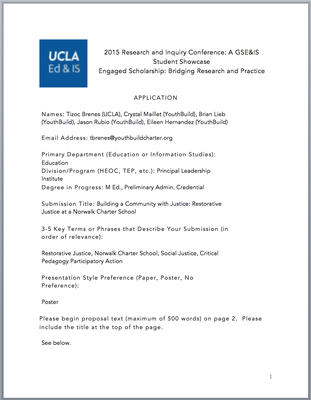

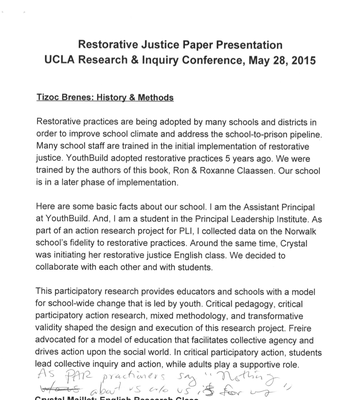

The restorative justice class in Norwalk had a second opportunity to share our work with the broader education community. Three other students, the teacher, and I also applied to present a paper on our participatory action project at the UCLA GSEIS Research & Inquiry Conference. We collectively filled out an application that explained our project, methods, the significant of our research, and results so far.

After our proposal was accepted, we collectively wrote a paper describing our project and created a PowerPoint with our research. The Norwalk students and I spent almost two week writing this paper, which added up to approximately 8 pages. Each presenter wrote and presented on a portion of the project.

Below is an image of the first page of the paper that we presented at UCLA:

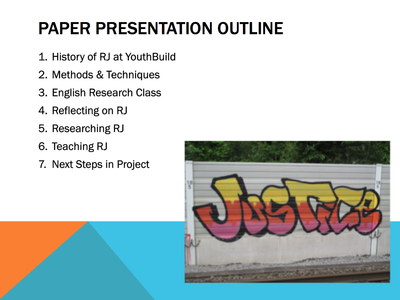

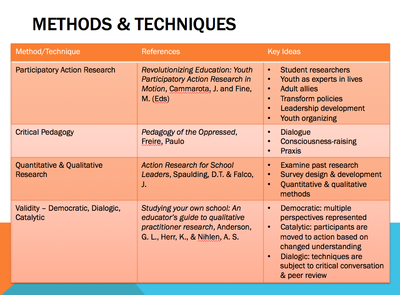

Below are images of the first 3 slides in our PowerPoint:

At the conference, we presented to a room full of graduate students and professors of education at UCLA. The facilitator, Professor Karen Quartz, noted that we were the only group presentation and the only presentation that included high school students at that conference.

After the conference, the Norwalk students indicated that they were proud of their accomplishment. None of these students had ever presented to such a large group of people or to professionals. They all expressed interest in presenting at another conference or forum. Clearly, they developed new identities as student researchers and education activists.

PARTICIPATORY ACTION (PAR)

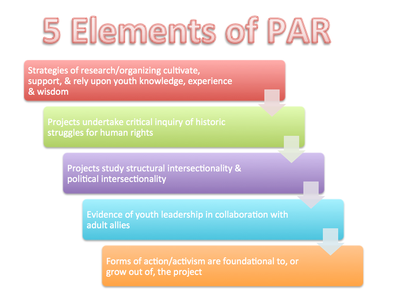

Participatory action research models were used to develop a current practice at YCSC, which we call community action. There are key differences between participatory action and community action. An article, titled “Critical Youth Engagement: Participatory Action Research and Organizing,” takes a critical stance toward “traditional epistemologies” that privilege university-based research (Fox, Mediratta, Ruglis, Stoudt, Shah, & Fine, 2010). The authors explore the “intersection of youth organizing and youth-led research” through case studies of student organizing projects and a project developed by the authors of the study (Fox et al., 2010). Research, in this model, is an opportunity for civic engagement; it is explicitly aimed at transforming educational policy by being shared with, for example, a principal, officials from the criminal justice system, or a school board.

The researchers developed a research matrix for analyzing critical youth engagement, which lists 5 elements in their project framework:

YCSC teachers, like those engaged in participatory action, seek to develop core academic skills in a social justice organizing context. Each YCSC campus develops 2 to 3 community action projects each year, which are a culmination of learning activities, an authentic assessment of learning, and an opportunity to make an impact in the community. The YouthBuild Charter School community action model can be improved in 3 ways: 1) developing rigorous academic skills in an academic research context, 2) engaging youth as leaders of, rather than volunteer in, these projects, and 3) seeking not only to engage communities, but also to change social and political policies.

Before implementing changes, I wanted to observe and analyze the first 2 community action projects implemented, in the fall and winter, at El Monte and Norwalk.

El Monte and Norwalk typically organize community action projects that are events, such as resource fairs, cultural exhibits, or field trips. Such events create an engaging, positive, and celebratory school culture. They also provide authentic assessments of learning and authentic learning environments for students. Even so, these events are not in the spirit of community action.

In the fall, the El Monte staff organized an event, titled Narratives del Barrio. On the evening of the event, elders from the community were invited to share their stories about growing up in El Monte.

This event also showcased student work, including two projects that were initial forays into community research. Once course asked students to interview a member of the community who came from a different ethnic/racial background than the interviewer. Another course asked student to take photos of their neighborhood and write poetry of fiction inspired by that photo.

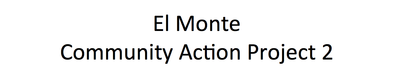

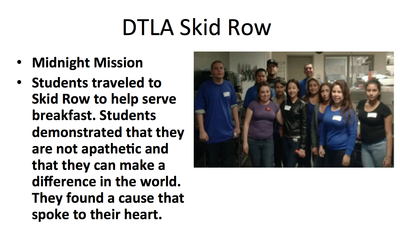

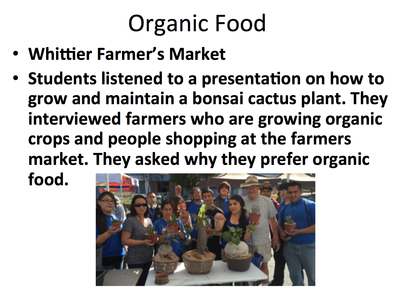

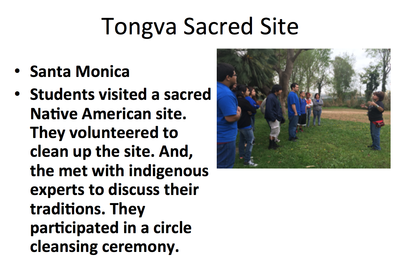

In the spring, for its 2nd community action project, each El Monte teacher took a small group of students on field trips. One field trip visited a homeless shelter in downtown Los Angeles, where student volunteered to serve breakfast to the homeless.A group of students visited UCLA, where they were hosted a student organization that promotes Latinos in the sciences. A third group attended an El Monte city council meeting. And, a fourth group visited a Tongva sacred site.The final field trip took a group to the Whittier Farmers Market, where students learned about organic farming.

In the fall, the Norwalk staff planned to host the students from another YouthBuild campus, in Long Beach, for a day of training. Students created leadership trainings for each other. This event did not take place, because of a last minute emergency at the Long Beach campus.

The following outline was created by the Norwalk teachers as they planned the event:

In the winter, for its second community project, the Norwalk staff members and students went on a field trip to Big Bear to collect ecological research and samples for scientific research. The Norwalk school staff also took this opportunity to facilitate community building and leadership activities with students.

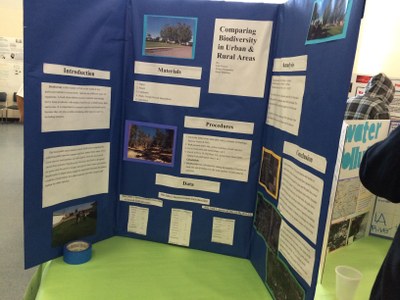

That ecological research was later used by Norwalk students in their YouthBuild STEAM Fair presentation, which won 3rd place in competition against other YCSC school campuses.

After observing the first two community action projects at each site, I aimed to create a third project that would be modeled after participatory action. My work with El Monte and Norwalk aimed to move beyond events and field trips and toward authentic community action.

PAR Project Implementation

YCSC staff members typically begin to plan their community action project months ahead of time. After I initiated my fieldwork project, the El Monte and Norwalk staff had already planned their 1st and 2nd projects. As such, I focused my fieldwork on these 3 tasks:

- Assessing community action projects

- Training staff on participatory action research

- Planning the 3rd community action project

The assessment of the community action project is summarized in the section above. With the staff members at each site, we looked at the projects and discussed how they compared to participatory action research. I used the a book, titled Revolutionizing Education: Youth Participatory Action Research in Motion edited by Cammarota and Fine, as my primary reference.

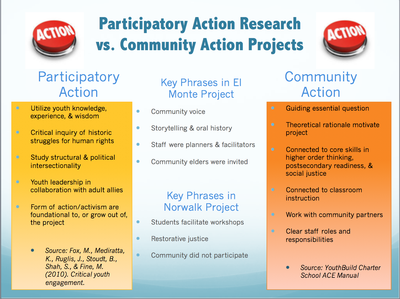

In this graphic, I compared the first community action projects at El Monte and Norwalk to the participatory action model. This graphic was used as a discussion point with staff members.

For the 3rd community action project, El Monte organized a community fair, titled Cafe y Cultura. This has been an annual affair for several years. This year, the teachers implemented 3 practices inspired by participatory action models: a) youth research, b) student participation in designing the project topics, and c) student participation in organizing the fair. Over 50 people, including students, parents, and community members, attended the fair.

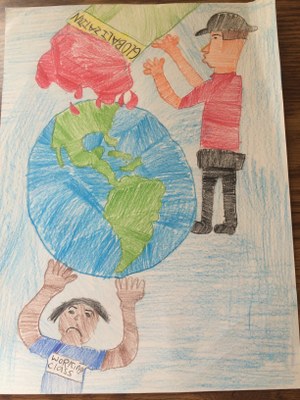

Students shared research that they had conducted. In an Economics class, students researched the economic impact of globalization. As part of a research essay, students wrote about how globalization impacted a family member, friend, or acquaintance. One student wrote about how his mother lost her job at a company after it moved its operations to a foreign country. This drawing on globalization was created to illustrate the essay:

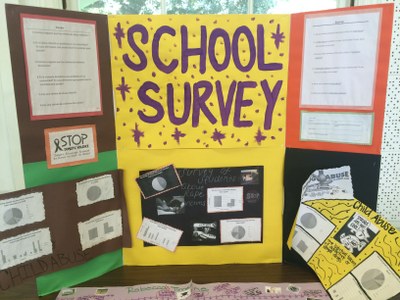

In an Algebra class, students were asked to collect quantitative data on issues that they deemed important. Students collected and analyzed data from their fellow classmates. The teams of student research took surveys on issues of sexual violence, geography, drug use, and child abuse.

One group of students in Algebra gathered social investigatory research on the city of La Puente. This community, adjacent to El Monte, was selected because one student lives in this area.

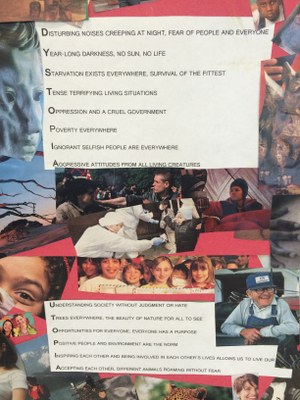

An English course tasked students with reflecting on their conceptions of utopia and dystopia. While some reflection were poetic and philosophic, others identified very specific political, social, and economic issues that need to be addressed.

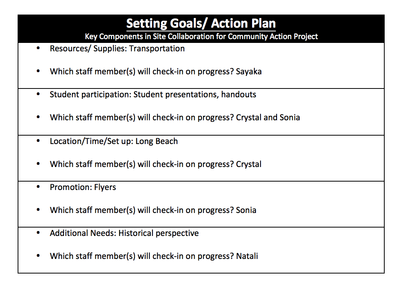

In Norwalk, the students and staff members participated in the planning of a Global Youth Service Day (GYSD) event. This event was primarily organized by and hosted by the YCSC campus in Compton. A teacher at that campus applied for and won a small grant to host a two-day event. Both days were planned collaboratively with students, teachers, and community partners. Planning sessions were held for several months on Friday afternoons.

I

This Compton teacher applied for the grant and served as the primary facilitator of the event:

The first day of the GYSD consisted of two parts. During the first part of the day, over 100 students and community partners formed leadership circles. In these circles, we had discussions about issues we face in our communities. Then, we created a list of community issues, such as police violence, violence against women, and lack of resources. The groups then had a discussion about how those issues might be created addressed or solved. We then wrote a list of solutions.

Each group sent a representative to the center of the room to create a list that compiled all of the problems and solutions identified:

After the event, the Compton students would present that list to the Compton Mayor. Compton students are members of the youth council for the city. They planned on using the collective ideas of the participants at GYSD to guide their work.

During the second part of the first day, students participated in workshops. One workshop was led by a UCLA Community Programs Office. This workshop used poetry to explore issues of identity and community change.

Another workshop was led by a local sheriff officer. She trained students in their rights. The third workshop covered the same topic, basic rights when confronted by law enforcement. In this workshop, students from a YCSC campus in Lennox facilitated the training on rights. Lennox student developed this workshop as part of an English class:

During the second day of the Global Youth Service Day, students completed community service at the school and at a local community organization. In this image, students helped muralists paint a community mural on the campus of their school:

Both El Monte and Norwalk staff members reflected on the community action project process. They provided me with feedback on challenges they faced designing their projects according to participatory action. Some of those included

- Resources

- Training

- Time

- Support from nonprofit partner

I also surmise that they had not yet developed the critical consciousness to center their work around transformational community change. The El Monte project was still modeled like an event, a showcase. And, the Norwalk students and staff were participants, and not leaders of, a participatory project. The new integrated learning model and the new trainings being planned to support community action, I hope, will spur both campuses to aim for more transformational work. This new model is described under the project webpage titled "Integrated Learning."

SUMMARY REFLECTION

Initial steps were taken to adopting transformative practices at two YCSC campuses, El Monte and Norwalk. Through critical inquiry, the staff and I identified reflected on our identity and how we addressed identity through our curriculum and practice. We dialogued about restorative practices at each campus and engaged staff members and students in improving those practices. And, through a study of participatory action research models, we thought of ways to align our community action projects closer to community research and frameworks.

Most importantly, we have built a foundation to further develop this work during the next school year. In the coming year, I would like to implement aspects of Transformative praxis at all YCSC campuses. Additionally, the following steps will provide the knowledge and skills to acts as transformational educators in the communities where we work:

- Evaluate restorative practices at all YCSC campuses

- Provide more training in circle facilitation

- Provide tools and training for participatory action research

- Continue to hold critical inquiry and positionality dialogues

- Gather and study data around issues of gender at school